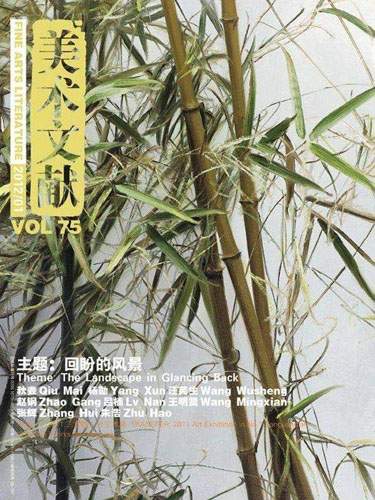

第75期 回盼的风景(2012年)

学术主持:唐克扬

主题:秋麦 杨勋 汪芜生 赵钢 吕楠 王明贤 张辉 朱浩

新作:冷军 张轮 龚余辉 庞璇

Issue No. 75(2012)

Theme: The Landscape in Glancing Back

Academic Host: Tang Keyang

A.t: Qiu Mai, Yang Xun, Wang Wusheng, Zhao Gang, Lv Nan, Wang Ming Xian, Zhang Hui, Zhu Hao

A.N: Leng Jun, Zhang Lun, Gong Yuhui, Pang Xuan

回盼的风景

学术主持:唐克扬

风景摄影也许不仅仅是摄影的一种,它或者是一种完全不同的摄影,或者是摄影的全部。肯尼斯•克拉克著名的《风景论纲》中开宗明义说:“风景不是一种艺术样式,而是一种媒介。”从这个意义上而言,摄影简直就是风景题材的最佳载体。银盐感光能呈现为自然的幻象,这件事本身已够奇妙,够不可思议了,因为“外在”的世界看起来不需要柏拉图山洞外迂迤的折光;用微小灰黑颗粒的排布使得天光树影宛在眼前,与其说是“再现”(representation),不如是浑然的“呈现”(presentation),换而言之,风景摄影不是成就了摄影而是塑造了风景自身。

在风景摄影中射入的不是密室之光,也不是上帝之光,因为上帝已在世界中了。

我们的专辑所讨论的主题更进一层。和上面讨论的思路类似,某类貌似“旧”的当代风景摄影不仅仅是风景摄影的题材之一,用一个世纪前的外国传教士和植物学家使用过的湿版术,把镜头重新对准他们观察过的丘陵、天空和河流,也不仅仅是一种偶然的时空重叠。有意或无意重温“早期摄影”所处置的情境,或是使用它们的技术,就像是驾着不用现代动力的“哥德堡”号再作东方之旅,它事实上是在回溯整个摄影向人类艺术传统提出的问题:我们在这篇文章中反复提及的“早期”这个属性事实上不是原影所天然具有的,而是现代人的回望而造就的,同样的,“老照片”或是“拟老照片”中脆弱的物理品质也不仅仅是因为“文物做旧”一类的处理,而是源自它们表征着消亡的、已经“存在过了”的事物这个当然的事实──我们想想,这不恰恰就是摄影本身所具有的品质吗?

风景摄影比室内摄影更接近摄影的独具品质,是因为它毁坏了真实和表征之间的桥梁,使得它们合而为一了——毁坏的祸首通常绝不出场,而废墟总是在那里。具有这样典型品质的风景,通常是蛮荒的,郊野的而非真切的,人情洋溢的。在中国当代所涌现的“拟旧”风景摄影更是如此,它们通常会涌现一种“天荒地老”的情貌,浑浑噩噩,不可言喻──也许这是因为这样的风景距离马远、夏圭、比斯蒂、格里茨,距离普桑和洛兰更远。当代的摄影技术对清晰程度和信息量孜孜以求,似乎又回到“逼真”再现的老路上去,而这样的风景照片追求的则是一种自我开杈、侧生旁枝的“传统”,它们寓意的“早期”其实是在未来之后。中国的“早期摄影”发轫于世纪之前。1906年,一个名叫足立喜六的日本人受末代清政府的聘任来到陕西高等学堂任教。足立喜六,出身于日本静冈县的科学教师,本来并不是一位职业历史学家,可是受到他的前辈学者桑原骘藏的启发,开始有计划地探访西安附近的汉唐旧迹:“……在桃李花落的傍晚,东海孤客独自徘徊于未央宫遗址上……俯视脚下两千多年兴废的历史陈迹,不胜感慨之至。”他的发现终在1933年汇集为一大本出版,谈得上是一份图文并茂的准考古报告──《长安史迹考》。摆在我们面前的百年之前的照片通常看不出年头也辨不出季节,灰黑氤氲的调子里隐藏的阴影,像极了春天里蒙蒙的田塍和烟树,但也可能是秋冬萧肃的风景而无从定论。近景里蜿蜒曲折的道路,仿佛是荒野中无心踏出的人径;远山起伏的身影,把广袤大地的进深扯成了一排互不相属的平行线,几乎没什么建筑物,点缀着连绵不绝的天际线的,是两座看不清面目的中国宝塔。如果不告诉你,那两座宝塔分别叫做大雁塔和小雁塔,大概没有多少人猜得到这张照片的拍摄地点。

摄影机镜头中的老西安是黑白萧条的,其实,这一切的后面本是片色彩饱满的画面:

“五六月间,眺望西安郊区,早熟的小麦在阡陌间泛起黄色的波浪,火红的罂粟花点缀其间,显得十分美观。在滴绿的白杨树下,驴马懒洋洋地拉着水车,给高粱地浇水……”

其实,在中国,这种由法国人尼普斯和达盖尔肇始的西方“影戏”叩关已久。几乎是在法国政府宣布放弃对摄影术专利控制的同时,万里之外的“满大人”琦善就在鸦片战争的战场上看到了这项意义深远的发明。但足立喜六来到的20世纪初叶是敏感的,那也是虎视眈眈的列强的远征队踏遍中国西省的时光,这群本身就是“先进”代名词的外国观察者不是一般的访古寻幽,他们勘测着从眼前到想象的距离,毫厘必较,他们使用着古人前所未见的仪器──摄影机。

从灰黄到亮丽,从外来者的眼光到本地人的自审,足立喜六的记录和当代摄影师的同类作品放在一起,它们的差别是明显的。仔细端详,我们会发现其中的奥秘──足立喜六的画面中显然缺了点什么。是的,那里找不着太多“人”的踪迹。《长安史迹考》的图景中,连绵冷峻的城墙外几乎看不到人烟,人们很难相信,这是一座当时人口近二百万的西北大都会。人们大概更想不到,远在一千年前的隋唐时代,这座城市的人口就已经远远地超过了世界上的大多数城市。在清末,西安的人口虽然显著上升了,它的面积却已经缩小到唐代长安的八分之一,并且,最重要的是,这样的城市被一圈严重匮乏形象的城垣所圈定。晚清西方摄影师的镜头中的中国由此分为两个截然不同的部分:可以“看见”(sensible)却“看不到”(visible)的十丈红尘里过活的人生,可以“看到”却“看不见”的萧瑟人世外的风景。

新的摄影术的意义不在于“发现”这种风景,而在于达盖尔等发明的令影像永久保留在物体上的方法。这使得中国人在潜移默化中面对一种不同的观察世界的视角。那是诞生伊始便显得熟悉又陌生的“新的经典”──因为曝光时间极长(最初大约需要20到30分钟),具有永固品质的风光是早期摄影的重要对象之一,长时间曝光使得照片呈现一种浓重的灰黑调子,反差极大,而且拍摄下来的景物看上去格外地“静止”,部分照片中因此而“空无一人”。它既是对所摄取的景物一定程度的忠实再现,又因总合了它不同时刻的特征,而和对象拉开了距离。依习惯了古典主义写实风格的西方人,那些被过滤掉的色彩信息(足立喜六的早春景色)或许有点可惜,对于已认同“绘事后素”的中国人而言却是一种意外地通往“真实”的途径,而且他们对摄影中体现的时间性的因素丝毫不觉得奇怪。

早期摄影首先是“借靠”上了一类在中国晚期视觉文化中流行的题材──它们的重叠也许不能完全算是偶然──在20世纪以来,诸如黄山这样的自然风景“意外”地成为一种富有中国特征的摄影主题。也许是因为早期摄影和它对象间的关系恰好沟通于近世中国山水画中异军突起的一类现象。被某些人称为“黄山画派”的皖南艺术家和他们的创作主题之间本有这样的关系:首先黄山是一个真实的地点,在地理构成上昂然独造,和周围的山系判然有别,构成一个作为观察对象的独立客体的理想条件;其次,这个“世界外的世界”同时是艺术家生活的地点和描摹的对象,在朝代更易的重要历史时刻突现的文化情境,使之极少和孤寂的图绘风格切题,和早期摄影“削减”的特征相符;最后,最重要的一点是“生活模仿艺术”,有关黄山的艺术作品不仅仅是在描摹自然的某一幅“小照”,它实际上也是有关此山的一切的“特征合成像”,云海,怪石,孤松……它们在总体上,而不是局部里构成了黄山的艺术呈现,而且全面影响到后来的人们从苍莽中寻求他们的形象。

这一切都使得有关黄山的摄影照片成了一个说明早期摄影对于艺术观念影响的绝好例子。和欧·苏利文的西部摄影有所不同(它缺乏既有的艺术惯例支持),和吕楠著名的西藏摄影也有所不同(在此我们扮演了旁观者的角色),有一类中国风景其实是在“中间”的。它既不是郎静山式的竭力回溯,一味向已有的艺术惯例靠拢,也不是绝对的“异域”风景,这种呈现和既有的现实确实有所重叠,只不过在彼此交汇的时候,它不是像郎静山的“画意摄影”那样消弥冲突,而是突出了摄影杂有的强烈的时间性和传统绘画的无时间性特征间的矛盾。

在此,再次强调一下我们讨论所涉及的时间差是很有必要的。为什么是在当代讨论“早期”?这是因为只有在鲜丽活彩的此刻,早期摄影所涉及的问题才显得如此昭彰:它首先面对一种发生已久的事实,其次更是关于一种“将来完成时”,关于不断喷涌而出和我们拉开距离的即刻的历史。如此,我们回头来看篇首西方人眼中肃穆遥远的中国风景,便不是回溯,而是前瞻,因为所有的改变正是由此开始。

The Landscape in Glancing Back

Academic Host: Tang Keyang

Landscape photography probably does not only belong to, but also is a totally different kind of photography, or the totality of it. In his famous Landscape into Art, Kenneth Clark makes the theme clear at the beginning, “landscape is not an art style, but a medium”, in which sense photography serves almost as the best carrier of landscape subjects. The silver-print can present the illusion of nature, which is so intriguing and amazing, because the “appearance” of the world does not need the reflected light outside the cave according to Plato. The arrangement of tiny grey and black granules perfectly “presents” rather than “represents” the skylight and the shadow of the trees to us. In other words, landscape photography does not make photography, but shapes landscape itself.

The light that shines into landscape photography is not from the secret chamber, nor does it come from God, for God is in the world.

We will further our theme in this issue. Similar as the train of thoughts discussed above, some of the modern landscape photography that appears to be “old” is not just one subject of landscape photography. The photographers employ the wet-plate photography used by the foreign missionaries and biologists one century ago to shoot the photos of hills, sky and rivers observed with their camera lens, which is not just occasionally overlap of time and space. To brush up the situations dealt with by “early photography” intentionally or unintentionally, or to employ its techniques seems to make an oriental journey again in the East Indiaman Gotheborg not navigated by modern power. Looking back upon the history of photography, it actually proposes the question to the art traditions of mankind: the attribute of “earliness” repeatedly mentioned in this article in fact does not belong to the early photography, but is made by the looking back by us in the modern times, so is the same with the fragile physical quality of those “old photos” or those that “imitate old photos”. Thus, this fragility derives not from “the imitation of the antiques”, but from the certainty that they symbolize the object which was dead, and which “existed”—isn’t this exactly the quality that photography should possess if we think thoroughly?

Compared with interior photography, landscape photography draws itself nearer to the special quality of photography, for it destroys the bridge between the truth and the appearance and combines them together—it being absent often, the ruin always stays there. Landscape with this typical quality usually exposes its wildness and wilderness instead of sincerity and humanity, so does the landscape photography that “imitates the antiques” in modern China. There usually emerges a drifting and muddling state of mind as if it were the end of time and the whole world faded away, which is so ineffable—perhaps, it is because the distance between this kind of landscape and Ma Yuan and Xia Gui is much farther than that between Joseph Stiglitz and the paintings of Poussin and Lorraine. Assiduously pursuing the clarity of the image and the amount of information, modern techniques for photography seems to return to its old way of the reproduction of “vividness”. In fact, this kind of photography seeks a “tradition” with side branches; the “earliness” embodied refers to the future. The “early photography” of China can be traced back to the beginning of twentieth century. In 1906, appointed to a teacher in Shaanxi Institute of Higher Learning, a Japanese, Adachi Kiroku, who was born in Shizuoka and who used to teach science came to China. Enlightened by a predecessor scholar Kuwabara, he began to visit the historic sites of the Han and Tang Dynasties in a planned manner, though he never was a professional historian: “…one evening, when the blossoms of the peach trees and plum trees fell off and drifted in the air, a solitary guest from the East Sea lingered among the relics of Weiyang Palace…Looking down on the historic sites that rose and fell in the past two thousand years, he signed with emotion.” He finally complied all the discoveries into one book in 1933, which was definitely an archaeological report-to-be with informative illustrations—A Research of the Historic Sites in Chang’an. We can hardly distinguish either the year or the season from these photos taken one hundred years ago. The shadows hidden in the dark, grey and steamy air resemble the fields and the trees with layer upon layer in a drizzly spring, while it also very much likes the desolate landscape in autumn and winter. In the close shot, the zigzagging road looks like a pathway casually made by the steps in the wilderness; the undulating figure of the mountains far away merges together with the vast land, forming several parallel lines that never reach each other. It is difficult to detect any architecture except two vague Chinese pagodas which decorate the continuous skyline. Barely can most of the people figure out the spot for photography without being told that these two pagodas are the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda and the Small Wild Goose Pagoda.

Though in the bleak color of black and white, the ancient Xi’an behind the camera lens actually unfolded a colorful picture:

“In May and June, looked into from afar and high, the early-ripe golden wheat ripple in the fields, the fiery-red poppy flowers dot here and there, looking rather beautiful. Under the white poplar whose greenness seems to drip, donkeys and horses languidly pull the water wagon for the irrigation of sorghum…”

Actually, long had two Frenchmen Niepce and Daguerre been knocking at of the door China with their western “films”; no nooner did the French government abandon the control of patent of photography than Qi Shan saw this invention with profound meanings in the battlefield of the Opium War. However, it was a sensitive time at the beginning of the 20th century when Adachi Kiroku arrived, and when the expedition teams of the western powers covetously and greedily trampled the whole area of the western provinces of China. As the synonym for “advanced”, these foreign observers did not visit the historic sites or seek serenity; instead, they surveyed with great exactness the distance between the sites in reality and those in imagination by means of the unprecedented instrument—the camera.

Once placed together, the records of Adachi Kiroku differ greatly from the works of modern photographers: the former are grey and yellow, the latter bright and shining; the former come from the view of an alien, the latter self-examination of the natives. Observing carefully, we shall discover its secret—obviously, something is missing in Adachi Kiroku’s photos; there are not many traces of “man”. In the photos of A Research of the Historic Sites in Chang’an, the signs of human habitation hardly appear outside the continuous and cold walls of the city. It is difficult for people to believe that this is a metropolis in the western China with a population of almost 2,000,000. More than we could imagine, the population of this city far surpassed most of the cities in the world about one thousand years ago in the Sui and Tang Dynasties. At the end of the Qing Dynasty, despite the obvious increase of the population in Xi’an, its area was reduced to 1/8 of Chang’an in the Tang Dynasty; more importantly, such a city was hooped by a circle of walls which severely lacked of good impression. Thus, through the camera lens of the western photographers in the Late Qing Dynasty, China seemed to be divided into two distinct parts: the “sensible” but “invisible” life far away in the human world; and the “sensible” but “invisible” landscape outside the bleak world.

The meaning of the new techniques of photography lied not in “discovering” this kind of landscape, but in exerting a subtle influence upon the Chinese who were confronted with a different perspective of observing the world through the introduction of the invention of the photographers like Daguerre who maintained the pictures forever on a certain object. This “new classic” turned out to be both familiar and strange to them since its birth—because of the long time of exposure (about 20 or 30 minutes at the beginning), the photographers chose landscape with permanent and stable quality as one of the important objects. The photos presented a rather thick tone of grey and black with great contrast; besides, the landscape taken seemed particularly “still”, thus, “not a sign of man” appeared in some of the photos. One the one hand, it faithfully represent the landscape taken to a certain extent; on the other it distanced itself from the objects by mixing those features at different moments. As for the westerners who got used to the classical realistic style, the information about the color filtered out (the landscape in the early spring from Adachi Kiroku’s works) was a pity. However, the Chinese who approved that “solid color overrides bright ones in a painting” regarded it as an unexpected approach to the “truth”, so the factor of time embodied in photography seemed nothing but normal to them.

Early photography at first “relies on” the popular subjects of the visual culture in the late Imperial China, whose overlap could not totally be counted as accidental. Since the twentieth century, natural landscape such as Mount Huang has “accidentally” become a photographical subject with Chinese characteristics, perhaps because the relationship between early photography and its objects is right in accordance with the phenomenon of the Chinese landscape painting rising suddenly as a new force. Regarded as “the painting school of Mount Huang” by some people, artists in the Southern Anhui has such a relationship with the themes of their creation: first of all, as a true site, Mount Huang distinguishes itself with the mountain system around with its special geographical structure, forming an ideal condition as an independent object to be observed; secondly, “a world outside the world”, it serves as both the living place and painting object of the artists. Its cultural situation, once emerging at the important historical moment of dynasty substitution, is hardly relevant to the desolate style of painting, which agrees with the feature of “subduction” in the early photography; last but not least, “life imitates art”. The artistic works about Mount Huang do not only depict a certain “snapshot” of nature, it actually reflect “the combination of all the features” of this mountain, such as the sea of clouds, picturesque rocks and legendary pines…In general instead of in part, they form the artistic appearance of Mount Huang, thus exert a full effect upon those who seek these images in the boundless world.

All these above make it possible for the photos about Mount Huang to become a perfect example that illustrate how early photography influences the artistic views. Different from the photographs about the west from O’ Sullivan, which lack of the support of the artistic tradition; as well as from the famous photographs about Tibet from Lü Nan (here we play the role as the observers), one kind of the Chinese landscape actually stay between the two. Neither does it endeavor to recall the past as Long Chinsan did, who draws close to the existing artistic traditions, nor is it the absolute “exotic” landscape, whose presentation overlaps the reality. However, it highlights the conflicts between the strong sense of time in photography and no sense of time in traditional paintings once it encounters reality, while Long Chinsan usually manages to mute the conflicts by his “pictorial photography”.

Thus, it is quite necessary to discuss the time difference mentioned above—why do we talk about “early photography” in modern times? It is because only at this colorful and splendid moment could the problems relevant to early photography be greatly exposed: on the one hand, it faces a fact that happened long ago; on the other, it is about a kind of “future perfect tense”, and a history that constantly gushes out and distance itself from us. So, when we go over the Chinese landscape in the eyes of the westerners at the beginning of this article, that would not be looking back, but looking forward, for every change starts right from this moment.